Stovetop cooking basics

Stovetop cooking is both a science and an art. The basic principles can be learned in minutes, but the subtler points take years to master.

A stovetop’s primary function is to put energy into a pot. There are two basic ways a stove can do this: by convection, which involves heating the air that surrounds a pot, or by conduction, which heats the pot itself. Nearly all stovetops use both methods; the difference between them is called the “thermal mode.”

Stovetop cooking is not the same as cooking on a stove. Stovetop cooking is like indoor rock climbing: it’s what you do in the absence of a better option.

Your goal when stovetop cooking should be to avoid using the stove. The aim is to find ways of preparing food that require no more pots or pans than you can comfortably fit in your sink at one time. It’s not just that you don’t want to let dirty dishes pile up; the real problem with washing dishes is that it keeps you from doing other things while you’re waiting for food to cook. Cooking on the stovetop makes this worse because pots and pans take up space over the sink, which means that while they’re dirty, they’re occupying space where you could otherwise be cleaning other things.

If you ever find yourself cooking on an actual stove, some simple rules will make it easier:

Put a lid on everything. This will reduce your cooking time by about a factor of three and will make it harder to overcook the food. And if the recipe says to “stir occasionally,” don’t. (This applies just as much when cooking on a stovetop.)

What it takes to be an expert cook with heat and oil.

I recently met a chef who explained that one of the things he had to learn in culinary school was how to handle a hot pan. This had never occurred to me, but it makes perfect sense.

Imagine you have a pan on high heat with some oil in it. You add some chopped garlic and wait for it to cook.

-If you leave it too long, it will burn. But if you take it out too early, it won’t have any flavor at all.

-How do you know when to take the garlic out?

You could do some experiments. You could try taking the garlic out at different times and then taste the results. Eventually, you would be able to make garlic that tasted good—but only after a lot of trial and error, and only if you had enough ingredients that you could afford to waste them experimenting. And even after all that practice, there’s no guarantee that your results would generalize: maybe the stove you were using is hotter than other stoves, so what works on that stove won’t work elsewhere, or maybe your tastebuds are less sensitive than average and what tastes fine to you is bland compared to what other people can taste.

If, instead of experimenting haphazardly, you wanted to get good fast, there.

It turns out that sautéing is a specialized skill, one that requires much more practice than even I had suspected. -You can’t just throw a bunch of ingredients in a pan and stir them around. There are all sorts of things you need to know about how to get the heat right, about what kind of pan to use, about how big your pieces should be and how crowded the pan can be, about when to stir and when not to stir, etc. It’s not impossible to learn this stuff on your own, but it takes longer than you’d expect. This is why cooking schools exist.

Tell me the best way to heat a pan?

How to heat a pan?

You take a cold pan, put it on the stove, and turn the burner on. The parts of the pan that touch the burner will eventually get hot. Then so will the rest of the pan.

But why wait? Why not just blast the whole pan with heat until it gets hot? This is what an oven does: it forces heat into everything in it by blasting everything with more heat than it loses.

-To put it another way: when you put something in an oven, you ignore all its thermal inertia. When you put something on a burner, you use all of it.

If you have a pan made of a good thermal conductor (e.g., copper), this doesn’t matter much; your food cooks about as fast in either case. But for most pans, there’s a big difference between using just the part in contact with the heat source and using all of it. If you want your food to cook faster, you should use more of your pan’s thermal inertia.

One way to do this is to make your pan out of metal that conducts heat better – e.g., copper instead of aluminum or cast iron instead of steel. But there are two other ways that are easier and cheaper: pay attention.

The best way to heat a pan is to heat the bottom side of it. -The best kind of pan to use is one that is essentially a thin layer of metal (stainless steel or aluminum) bonded to a thick layer of copper since copper is an extremely effective conductor of heat. The reason this works is that the heat will flow through the metal into the bottom surface of the pan, which will then conduct the heat efficiently into whatever you’re cooking. If you’ve ever flipped over a non-stick frying pan and noticed that it’s mostly plastic and light-weight metal, you’ll see why conducting heat through the sides doesn’t work well. It’s because things like plastic or even cast iron don’t conduct heat very well.

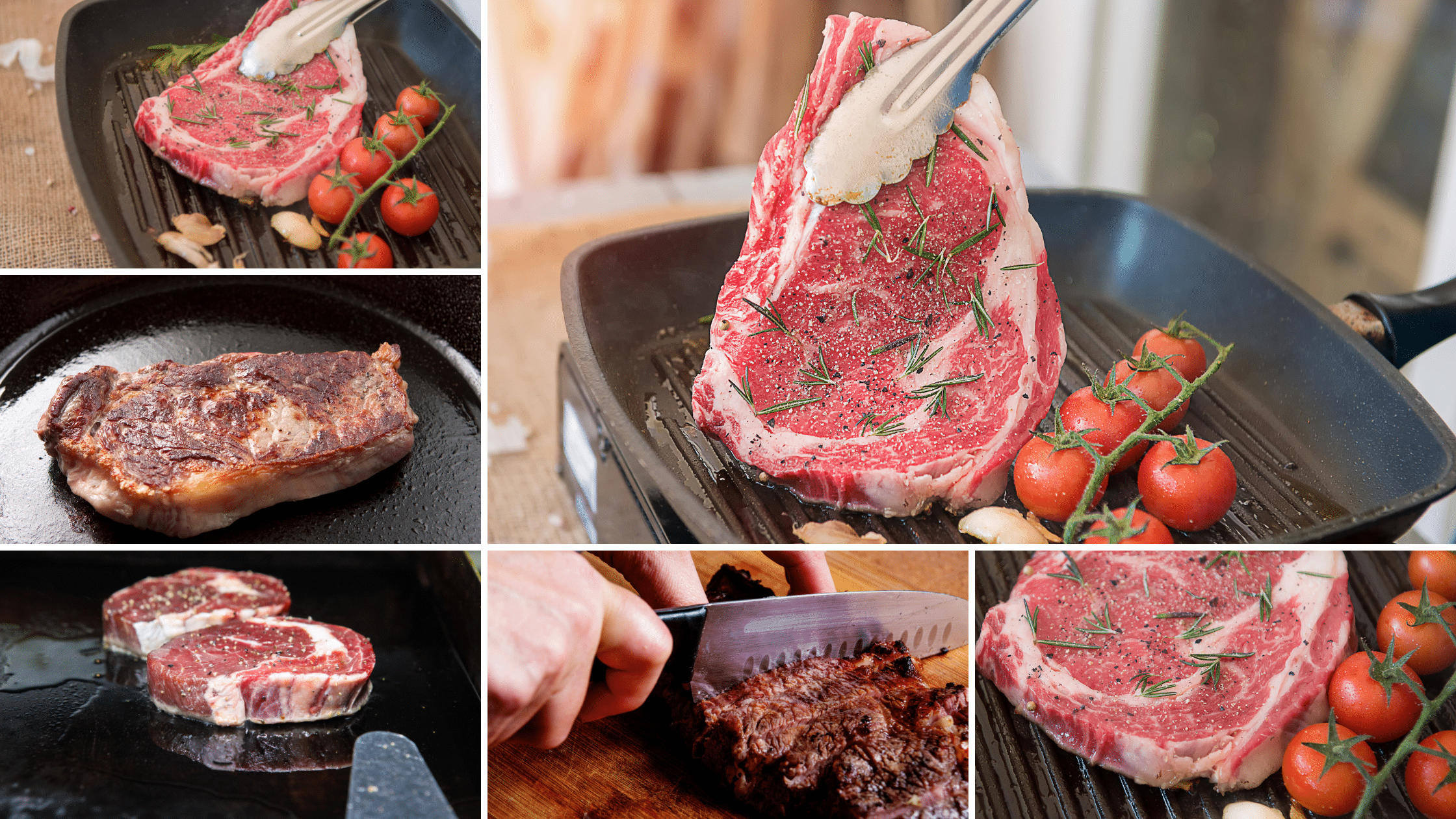

How to cook steak on the stovetop?

Pan-frying is the simplest technique for cooking a steak. I love preparing dinners with no recipe. The truth is that good food is more based on the technique than a recipe; the best dish is usually the most straightforward to prepare. The best steaks are cooked. You just need to add one ingredient to your steak recipe. It’s all about learning how to pan-sear. The Pan-searing process involves cooking a surface unharmed in a hot pan and then creating the desired crispy golden-brown crust. It helps add flavor to the dishes.